Module 2: Portraying Patients

Learning outcomes

At the end of this module you will be able to:

1. Define the vegetative state and explain how it is different from coma

2. Identify stereotypes of the vegetative patient in the media and recognise how these stereotypes differ from clinical realities

3. Analyse the implications of different ways of representing the vegetative patient (in the media, broader cultural representation and in family accounts of their loved ones’ condition).

Popular culture is full of images of people in comas, usually looking physically healthy, in a state of suspended animation, a ‘sleeping beauty’.. There are notable absences: of black or older people, and often a fetishisation of the young, female body.

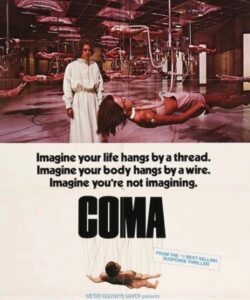

The patient is often imagined as a kind of sleeping beauty. The inevitable physical complications that come with lying unconscious for months or years are usually not represented. Film producers and scriptwriters have long been fascinated with the possibilities coma offers for creating powerful cinema. The original film called ‘Coma’, for example, was a horror film in which healthy young people are sustaining for organ harvesting. Based on a novel by Robin Cook, ‘Coma’ was released as a film in 1978 and again as a two part mini-series in 2012.

Whether or not it is the main focus, films often feature characters in coma, and even in films which are more ‘realistic’ than science fiction movies, the patients’ states usually bear little relation to reality. A study of movies showing ‘prolonged comas’ found that all the actors (with one exception) remained beautifully groomed, often tanned, and there was no muscle wastage, contractures, evidence of double incontinence, or even feeding tubes (Wijdicks and Wijdicks 2006).

2.1 Sleeping beauties

Families we spoke to were often critical of media romanticised representations of ‘the bedside vigil’ where an idealised image of a ‘coma patient’ serves as a cipher around whom the other characters can revolve: reading poetry, expressing their love, or revealing secrets.

Listen to Gunars describe visiting his sister.

Families expressed distress and frustration at the romantic image of the patient in a permanent vegetative state. The mother of Karen Ann Quinlan (an early famous case involving a young woman in a vegetative state) was sharply critical of how newspapers and TV reports imagined her daughter. She contrasts how her daughter was represented in the media and what she herself witnessed at the bedside:

“Most of the artists drew beautiful sketches, because the public wanted to think of her as a ‘sleeping beauty’. they always painted her with long hair …While the newspapers called my daughter ‘the sleeping beauty’ I sat by my daughter’s bed… A medical description in the court describes her “emaciated, curled up in what is known as doeskin contracture, every joint was bent…” (Quinlan and Quinlan, 1977, 215-222)

Creating alternative images

As researchers in the ‘Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre’ we became increasingly frustrated at stereotypical images being used by journalists or even journal editors to illustrate articles about this subject. Stock photographs used to illustrate articles include clasped hands (which have the advantage of illustrating care and being anonymous but say very little), brain scans (often showing bits of the brain ‘lighting up’) or beautified sleeping beauties (in one case a painting of Ophelia floating among flowers!) We therefore worked with artists to produce different types of representation. Throughout this course we’ve used the artwork of Tim Saunders and the shadow theatre imagery of Karin Andrews Jashapara (see below). These original representations were produced in collaboration with us, the artists developed the images after listening to some of our interview data with families. (You can find out more about this in the unit on Creative Collaborations).

Image by Karin Andrews Jashapara

Image by Tim Saunders

Activity 1

- Look back at the picture you drew of a vegetative patient at the start of this course. Do they look peaceful? Are there any signs of contractures or any other physical problems? What was the source of your visual imagining of the patient? You might want to add a comment to the section at the very bottom of this page or have a look at what other people have said.

- How do you respond to the images presented here created by artists in response to listening to family accounts?

Click here for Activity 2 - Additional Option. For Journalism/media studies students (when this course is part of a degree programme)

(Estimated time 40 mins)

Note: Optional activities are offered in many units. These are not part of the core cumulative learning for the online course (short version), but can be pursued if they particularly interests you or fit into a programme of study recommended in discussion with a tutor.

If you doing this course as a formal part of a University degree programme then read the research article by Wijdicks and Widjicks (2006) “The Portrayal of coma in contemporary motion pictures”. You can find the full reference and link to this study (and all the other sources we cite) in the penultimate Unit of this course called ‘Resources’.

22 Comments

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I really like the images! I’ve experienced how difficult it is to find accurate images of comatose and vegetative patients, so I really appreciate the ones you found!

I think the images seem a little distressing – showing suffering ? I think if the patient is in a vegetative state they aren’t suffering as they have, by definition, no awareness and whilst they may not look peaceful they have no awareness. It may be indeed difficult for the family to see, which is understandable, but the effects should be carefully explained and family reassured that they are not suffering. I think there should be middle ground between the image of resting quietly given by the media and some of these images which look a little grotesque perhaps. I showed it to my husband and he said it looks like a murder scene so perhaps a little softening?

I felt the same Helen when I’ve done previous courses. I find the pictures look quite ‘tortured’ and disturbing. Granted our patients aren’t always peaceful but I agree we should also emphasis that we don’t think people in vegetative states are in pain or suffering.

I would add that families are also contributing to media representations. For instance in some recent cases parents have released pictures of their children looking peaceful and merely sleeping.

Thank you – really interesting how these comments already picked out issues around the source of an image, its context and interpretation and the implications of different images. The artists who produced these images did so after listening to interviews with family members we interviewed and they attempt to give visual representation to those voices. The question of perspective is indeed key. There’s more about this in the unit on the ‘Politics of visualisation’.

While I drew in the various medical procedures/equipment that may be attached to and supporting the patient, the person I drew was still simply laying on their back in a hospital bed — likely a reflection of not wanting to consider how all of those medical devices actually affect the patient, as is the procedures are happening to the patient but the actual impact is still romanticized to make the onlooker more comfortable accepting of the situation.

As the wife of a PVS patient I didn’t find these images gruesome – upsetting yes because they were realistic depictions. The one by Tim Sanders resonated particularly with me – that could be Al lying on the bed.

Interesting comments about PVS patients not suffering. I would respectfully disagree. I have no clinical training and am certainly not objective of course, but I sat with my husband for thousands of hours. He didn’t like being moved and when he was dying i could defintely sense some physical agitation. He may not have been able be process this as a non PVS patient would, but it is still suffering. Of course, we can never know how much he knew or felt if anything – and therein lies the crux of a family’s pain (apart from the loss of that person). I also feel that it’s important to show it as it is – depicting it unrealistically/kindly doesn’t reduce a family’s grief because ultimately they have to go through it and see their loved one like that. They see it first hand, day in, day out – and no picture can be worse than the reality of that.

Thank you for sharing your perspective. I am sorry for his and your suffering. I was Karen Quinlan’s age at the time and I remember her and her parent’s ordeal and hearing directly from her mother that her daughter’s condition was not as the media depicted it. It must be difficult and frustrating to know the reality and feel that pain as well as the pain of the media’s false portrayal.

That is interesting but by the very nature of VS the patient is t in pain As they have no awareness- if the patient is in MCS then being in pain is definitely a possibility- this is where proper assessment by a team and involvement of family all the way is required to identify what awareness they may have and what they may or may not be aware of. Your observations of pain would be listened to carefully and explored and perhaps the diagnosis reviewed based on this?

To be honest, we were never given a definitive diagnosis. We were told vegetative, possibly minimally conscious but the term applied didn’t seem to be considered that important. While the staff were supportive, we didn’t get a lot of information and didn’t really know what questions we should be asking.

The picture I drew was someone still in a bed with a frown on their face.There’s no sign of physical problems from my drawing. The paintings and drawing are very moving. The image by Tim Saunders hit me the most.They are realistic and moving.

I found pages 58 and 59 of the RCP guidelines helpful as they comment on pain which is understandably a huge concern for patient’s loved ones.

I found this section and the images within it very eye-opening. Looking at my own drawing, it was a representation of the “sleeping beauty” image. I was quite shocked looking back at this because my mother works within a hospitality and has told me lots of stories about patients in these states and at the end of their lives and how difficult, and not peaceful, it can be.

I am sure a lot of others would draw something similar to me, and if they hadn’t been educated on the realities of comas and vegetative states beforehand it would be very distressing to experience it for the first time.

Upon reading the Wijdicks and Widjicks 2006 article, I was shocked that 39% of viewers said scenes in films that represent comas and vegetative states could influence their real life decisions.

Impressed you are fitting the extra reading in Chloe – and thanks for highlighting that figure and reflecting on your own ‘sleeping beauty drawing’

Quite shocking how many people are influenced by TV, right? I remember one of my favorite movies with Reese Witherspoon Just Like Heaven where she is portrayed peacefully sleeping and no physical change even though she is in a coma for months. I also believed that coma is peaceful and waking up was easy, I was convinced in the speed recovery but reality is much more scarier. And can you imagine all the people influenced by the media and how disheartening reality is for them

I like the image of a silhouette on the bed. It makes me think ‘where’s the person that was there?’

That whole many permutated maze-like process relatives go through: Are they there? Are they the same person? Are they even a person?

Tim Saunders image of not fully being there has challenged my perception. Alongside the interview and how we can see every patient as the same and take away the individual from them. My image focused more on the emotions than the physical pain and side effects etc. So I found this very interesting and broadened my own understanding and knowledge.

Yes, I have a sleeping beauty image in my mind. These images seem to me to show harder for the relative than the patient themselves.

Even though i work with patients who are in a disordered state of consciousness, like Macy QS, i drew mine lying on his back and looking peaceful, with a feeding tube!!

The Tim Saunders´s imagem impacted me. It´s a trully hard personification about the suffering of tha patient. Shows me how we objected the pacient in vegetative state.

I went back to my drowing and it as a sleeping beauty! This course is opening my mind and make me think so many thing in relation to disability rights theory (with is my study field).

The connections with disability rights are key I think – and create some interesting contrasting imperatives to be negotiated – would love to hear more about what thoughts the course provokes in you in relation to your specialist theoretical areas as you move through the materials